- Home

- Gail Scott

Heroine Page 3

Heroine Read online

Page 3

Anyway, I decided to act confident. Aided by the fact that at that moment the door burst open and some hookers came in. They had snowflakes on their hair and eyebrows. To keep warm one of them was dancing wildly. Left foot over right. Until she saw you had your eye on me. She stopped and stared angrily from under her wide pale brow. Very French. And I noticed she had middle-class skin. Therefore no hooker, just one of your socialist-revolutionary comrades dressed up to help organize the oppressed and exploited women of The Main. ‘Possessiveness reifies desire,’ called a girl with green eyes to her from the next table. So young I hadn’t seen her. ‘Right on,’ I shouted. What did I have to lose? My last lover was a journalist who wouldn’t take off his earphones. And his sheets were full of crumbs. The fake hooker cut her losses quicker than I could have. By lighting a Gauloise and launching into a political analysis of prostitution and the city administration. No doubt the better to get your attention. But I was so busy noting the exquisite beauty of her French brow, wide lips and dimple on the chin that I failed to see, my love, how you were smiling at her as sweetly as you smiled at me.

We get up to go. Or at least I do and you follow. This was an essential moment. Outside in the fog we can hear the gulls calling from the harbour. The cold wind cuts. We start walking. The smell of cappuccino is wafting from some restaurant. I love the smell of coffee.

We’re on rue Notre-Dame. Maybe you’re testing my revolutionary potential for going against the system. Because you say, smiling: ‘Let me teach you how to fish in a junk shop.’ In a display window your hand sweeps away the ropes of pearls. There, on a plaster chest, a purple amethyst. ‘Yours,’ you say, flipping it in my pocket. Outside you pin it on my sweater. My guilty grin is due to the voice of an old woman behind us in the fog. Someone has snatched her purse. ‘Le policier dit que quand il porte son uniforme, les gens arrêtent de faire des mauvais coups …’ she says squeakily to her friend. ‘Mais quand il est en civil …’ We can hardly see her. But we know she’s under some sort of statue. Someone else giggles nervously. The old woman’s voice again:

‘Tu ris comme une bonne soeur.’

The lens sweeps down the stone steps leading from the chalet toward a street opening bulb-like into the mountainside. A grey woman stands up, pushing away her bed of pine boughs. Her hair is silver. Her stockings are stained. Her skirt is a filthy undeterminable colour of suede. She starts walking toward The Main, hugging a fence along a demolition pit. DOWN WITH GENTRIFICATION, says the graffiti. She turns the corner. The narrow street curves gently along a row of red brick flats. In some cases the paint on the doors is peeling off. Those with new cedar windows were recently bought by politically progressive university professors. The grey woman heads toward an empty lot and sits down on a cement block. WAIKIKI TOURIST ROOMS, CHAMBRES AVEC CUISINE, says a blinking sign.

On the bottom floor to the left, I’m lying in the bath. Watching how in the green five o’clock shadow the conflicting patterns on the rug and sofa dim. With the television flickering in the corner beyond the half-open bathroom door. It could be a scene from an old Hitchcock movie. For this is the eighties, but there is a terrible nostalgia in the air. People are buying those fifties lacquered tables with round corners for their kitchens. The couple is also back in the form of the new woman and the new man.

Except us, my love. Because sinking below the line of pain the way I did after we broke up (spring of ’79), then reconciled last winter, it nearly drove me crazy. I wrote in the black book: One night a little tipsy and we’re together again. I love you but there’s no spontaneous outpouring of the warmth I need so much. I drink. I want to take pills and run away. As-tu vraiment peur que je te mange, comme dit Marie? A little later, we had to break up again.

Shhh. Watch the depression. The solution is not to be burdened, as an F-group comrade told me back in ’76. When I got drunk and confessed to him I couldn’t handle it when the girl with the green eyes put one hand on my arm and the other on your bum. As if she were the shock centre through which passed our love. We were in Vancouver. Nature was so beautiful with the hibiscus blooming loudly. I wrote in the black book: Olympic Vacation, July 23. Arrived by train. The end of a long black corridor. Now I know joy is what I’m looking for. Learn to laugh. No matter what the circumstances, being burdened only makes things worse. Don’t be such a Protestant. At the time we were sitting in some wisteria eating a salmon a comrade had lifted from a fish vendor. In the photo I had a nasty frown between my eyes because of trying to explain why it was wrong to steal from the little guys. The comrade answered: ‘Under capitalism, you get it while you can. It’s sure as hell none of them is going to give any of us anything.’ From a transistor on the grass Janis’s voice rose up seconding the motion, singing grab love when it comes along, even if it makes you sad: ‘Get It While You Can.’ Actually, I feel fine as long as no one disturbs my peace. A knock at the door really makes me tense. After all, it could be anything. The welfare lady looking for a reason to stop my cheque. ‘Do you live alone? We hear you have a boyfriend?’ And I’d say just to get to her: ‘Nope, a woman.’ God I hope this place isn’t tapped like the one on Esplanade. With the RCMP listening in on every conversation. Of course it isn’t.

I’m probably just upset due to Marie’s visit. Six months’ absence and she walks in as if it were nothing. Being a woman who never looks back. Maybe that’s what Janis meant by it’s all the same goddamned day. Going with the flow. That Québécoise I overheard in the Artists’ Café had the right attitude. ‘It’s over,’ she told her friend.

‘Oh yeah?’ her friend responded from across the table. ‘Depuis quand?’

‘Depuis un an.’

‘Oh, I hadn’t noticed. No bitterness?’

‘Non, pourquoi?’

My love, I wanted to be that way. The better to save me from embarrassing moments like that time with all we women comrades. A woman’s party, I think. ’Twas near the end of the reconciliation and it was important to be cool. The girl with the green eyes came in looking sad and skinny. With a shock I noticed her hair was cut and with the side part she exactly resembled your mother. That’s how I began to think she was after you. ‘Women get old,’ I told her, ‘so they won’t be attractive to their sons.’

It was a stupid thing to say. But I was trying to control the darkness so I wouldn’t do something ridiculous. In my pocket was the blow-up of that article where Prince Charles, in announcing his engagement, said by way of explanation: ‘Diana will keep me young.’ I was thinking of pinning it on your door. Clandestinely, because when you saw it you wouldn’t find it funny. The idea came as I got up one silver morning, the snow melting so fast a Québec poet had written ‘Time is slush’ and printed it in the paper. You were coming to get the little Chilean girl we were looking after (her parents being illegal in the country). But what to my surprise did I see, as I peeked out the window of the flat on Esplanade, but the girl with the green eyes waiting on the sidewalk. Her smile was surprisingly warm. Still, it couldn’t have been easy. The eyes looked small and swollen as if from crying. And the mouth stretched, almost, in the pale face. I saw the large penis slip between our lips. I felt the soreness of the jaws after a while. This was just before that beautiful April scene where the two of you walked up the street like lovebirds. So when you came up for little Marilù and I asked you how come the girl with the green eyes was also at the bottom of the stairs so early in the morning, you said: ‘We’re all friends, we three, so why are you acting suspiciously?’

I said, the words sticking painfully in my throat: ‘Does friendship include, uh, sex?’

And you said: ‘We’re friends. And you’d know more if you asked less.’

Out the March window I checked her face once more. She looked scared she wouldn’t win. Just like I probably did in that last period of our love. The same face exactly. Except I knew my star was falling and hers was rising. That’s a defeatist way to see the picture. Actually, my love, when you said you were just friends, I

believed you. For people were saying she was a dyke. Besides, creeping through a corner of my mind was that funny little slogan: ‘To the victor belongs the spoiler.’ I should have said that to the shrink from McGill who said: ‘We need to find the darkness in you that makes you tolerate such a situation. A woman who loves herself doesn’t put up with a man who deprives her of affection.’

Instead I reminded her for the n th time a political woman has to be open. I repeated once more that the problem with therapy lies in its lack of social analysis. She listened as I pointed out how in coming up the winding oak stairs to her office I’d noticed the panelled walls of the English-speaking school of social work forbade protest with signs that said: ‘NO POSTERING; PAS D’AFFICHAGE.’ They had the same signs except only in French and pinned on the cement block walls at l’Université du Québec. But over there no one paid attention. The place was covered with graffiti. QUÉBÉCOISES DEBOUTTE. SOCIALISME ET INDÉPENDANCE. LE QUÉBEC AUX OUVRIERS. People were freer then.

The shrink, a jolly Aries with a round grey Beatles haircut, asked: ‘Is there any more you want to say before you leave?’

I decided to tell her about the dream. Because there were three birds but I couldn’t see the third bird’s face. Try as I might. It was very frustrating. The first one was a nightingale, very modest, sitting in the long grass in the grey dawn singing a beautiful song representing infinite poetic possibilities for the future. The second was attached to the first by a string. It flew up into the blue sky where the world could see. A painted bird, trendily attractive, chattering madly. But its song was thin. The third was sitting on a tree with its back to us. Fully developed and a beautiful singer. But we couldn’t see what kind it was.

The shrink said: ‘Gail, I think it’s pretty obvious, don’t you? The first one is the darkness, the night in you we talked about earlier. Still, it’s very beautiful when not obfuscated by the image of the second, the painted bird you are choosing to show the world.’

‘Very deep,’ I said sarcastically. ‘Anybody who has been a sympathizer of the surrealist movement can tell you how to read manifest dream content. The point is we have to create new images of ourselves even if at first they’re superficial, in order to move forward. Otherwise we’re sitting back there in the grey dawn. But what’s the latent content? What I want to know is who that third bird is?’

‘Well,’ she said, ‘when you do maybe you will have come full circle. You say the third bird is “fully developed.” I presume that means having transcended the two others. The third bird is your answer.’

I guess dream time is like train time. No line between night and day, yesterday and tomorrow. Waking up periodically on that trip to Vancouver, it could have been a dream. First the large blond woman from Keewatin in the powder-blue pantsuit drinking with the boys all night. Yet staying fresh as a daisy. She’d even left her children home and wasn’t worried. Often when I opened my eyes she’d be telling another joke about Indians or hunting. And once when I awoke a storm was blowing and suddenly out of the forest in a flash of lightning I saw written on a huge stone: ‘With schizophrenia you’re never alone.’ We were going through reserve country.

In the dark I thought how I’d like to capture that loneliness and write it in a novel. But it was already too late because the train was out of the forest and going through a giant field of car wrecks.

Car Wrecks and Bleeding Hearts

Clarity. The trick is to tell a story. Keeping things in the same time register. I go with you to Europe. There our love starts. Subsequently I get involved in heavy politics. Then we’re the left-wing couple returning home from abroad. Clothes perfectly cut yet appropriately dressed down: high boots, purple blouse, short leather skirt. The comrades are anti-couple. But in the bistro they can’t get over how good I look. ‘You’ve really changed,’ says one. ‘Les femmes rouges sont toutes belles,’ says another. The marble tables are laden with beer. Through the smoke I see the comrade’s pockmarked face in the mirror. The hypocrite. Still, my love, I wonder do I look good because your arms keep me from bleeding all over town in search of love? Like I was before.

Oh, Mama, why’d you put this hole in me? Stop. This is the city, 1980. A single raindrop squeezes out of the sky. Cut the melodrama, two lesbians told me back in ’77. They were in that crazy café singing of love in the telephone booth. So beautiful, so free. One had a thick lock of brown curls down her neck. The other with tiny fingers and red lips. When she talked her voice was that of a happy bird. I was writing it all in the black book, looking, granted, kind of sad. She said, mocking: ‘We hope the heroine of that story isn’t a heterosexual victim. Il y en a trop dans le monde.’

What did they take me for? Of course I know nostalgia can’t penetrate a real city. Maybe it seemed right as country and western coming out of a false-fronted restaurant near Sudbury. A girl was crossing a dusty village street. All decked out in a red velvet suit. Waiting for the small blue dot to come over the bridge. Larger and larger. But the two-toned blue Ford didn’t come. Mrs. Callaghan was hanging clothes on the line. Having a hard time raising her arms over her head because she was pregnant. Out of the door came the hairdresser son with his girlfriend whom he’d just done platinum blond. ‘Have you seen D (the boy with the blue Ford)?’ I asked worriedly.

‘No,’ they said, trying to look innocent. On the radio Hank Williams was singing ‘You Win Again’ about his cheating love, but he can’t leave. In the purple dusk the girl felt scared. Albeit a corner of her ‘mind rejoiced at relief from boredom. Coming up to the city she quickly adopted black clothing as a sign of urban sophistication. The next step was to cut the melodrama.

Black plus white is the colour of the eighties. Marie in her immaculate white silk on the sofa of my bed-sitter this afternoon was a portrait of the decade. The vermilion lips on powdered skin a Greek mask covering the face of the seventies feminist. Don’t be moralistic. It’s the heart that counts. Continuing my ablutions I could see, through the open bathroom door, her glance fix once more on the dirt and grease accumulating over the stove. Turning to me (at last) she says, almost angrily: ‘What are you going to do?’

I turn off the water, the better to hear. ‘Do? I don’t know. Write a novel maybe.’

Outside the black sneaker boots and black pants of a famous Montréal modern dance troupe go by the window.

‘You’ve been saying that for years. Fais donc quelque chose.’

I could do without the greasepaint. But what a mouth she has. Back when I cut the profile of a winner, we kissed on her bed. I was lying on top of her soft breasts. Then she pulled up her white nightshirt and pulled down her panties. But I rolled off. Swallowing the pain, she rolled a joint with her tanned fingers. It was the pot falling on the floor that gave her the energy to move forward. As if two negatives could make a positive, she stood up and said energetically: ‘Je ferai le ménage demain.’ As she ushered me toward the door. ‘Bonsoir,’ she said, turning toward me her beautiful Gallic profile. I went down the iron staircase. Under it, Québec Libre was fading on the brick wall. There was a bar-salon on the corner.

‘Rends-toi intéressante si tu veux avoir des amis,’ Marie adds.

As she stands up and moves toward the television, her expensive skirt falls around her thick calves. I’m not jealous, but a dress like that you can only buy on $40,000 a year. Maybe she sold out by going to work at the film board. That’s unfair. Bitterness will get you nowhere. Besides, high salaries and job security are the fruit of progressive union militancy.

’Tis nearly November. From the mountaintop the Black tourist watches the field of car wrecks below the skyscrapers. The old woman stands up from her bench and starts walking along the cement riverbank toward the city centre. At some point she turns and takes the street that runs up the middle. The Main. Her stockings are stained. Behind a postage-stamp ground-level window a light shines under a bushel. Sepia, I know that’s silly, but I can’t find the word. In the dictionary they call it a rudimenta

ry penis. Ohhhhh, dream, rising sap is the stuff of art …

Out the window that trendy dance troupe goes by in the other direction. They walk leaning forward, flat-footed. Like they were nearly falling off the world. In the Blue Café I heard someone say they dance as if the couple is back, except there is tremendous violence between men and women. Their choreographer is supposed to be brilliant. I saw him go into the lobby of the Cooper Building where artists live and where in the mornings the girls sun themselves on the front steps in black high heels and net stockings. He was wearing a white shirt and black pants and stood weighing an apple in his hand. Later, the young genius’s head could be seen at a fifth-storey window. It is said there is nothing in his room but a bed and a computer.

Through the bathroom door my little room looks overstuffed. But I like my tub. Oh, froth, stay warm now Marie’s gone. Maybe we’ll get somewhere. Looking at those feminists in the restaurant the other day who said: ‘We feel sorry for you, how long has it been since you’ve had a man?’ I made a terrible grimace. My lip trembled in self-pity. One had Madonna hair and big earrings. Although really it was all an act for I was thinking: ‘A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.’ I saw that slogan at a demonstration. Out loud I answered sweetly: ‘Ah, never mind that, it doesn’t matter.’ But they were women and could see the edge on my tongue.

Oh, my big mouth. My hungry mouth. Mother, why did you make this hole in me? Those were my thoughts on the way down from Sudbury. Actually, I was locked in a cubicle in the Ottawa bus station. Old tiles and oak panel doors. Later, they tore it down. ‘Do you speak French?’ said someone among the noise of toilets whooshing.

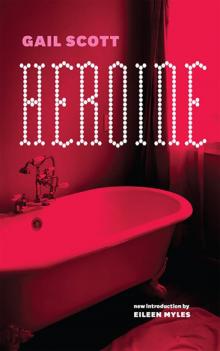

Heroine

Heroine