- Home

- Gail Scott

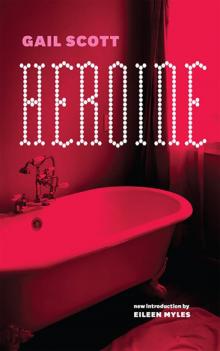

Heroine

Heroine Read online

copyright © Gail Scott, 1987, 2019

second, revised edition

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Coach House Books also acknowledges the support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Title: Heroine / Gail Scott ; foreword by Eileen Myles.

Names: Scott, Gail- author. | Myles, Eileen, writer of foreword.

Description: Previously published: Toronto: Coach House Press, 1987.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190141468 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190141492 | ISBN 9781552453919 (softcover) | ISBN 9781770566071 (PDF) | ISBN 9781770566064 (EPUB)

Classification: LCC PS8587.C623 H4 2019 | DDC C813/.54—dc23

Heroine is available as an ebook: ISBN 978 1 77056 606 4 (EPUB), ISBN 978 1 77056 607 1 (PDF)

Purchase of the print version of this book entitles you to a free digital copy. To claim your ebook of this title, please email [email protected] with proof of purchase. (Coach House Books reserves the right to terminate the free digital download offer at any time.)

‘We use signs and the signs of signs only in cases

where the things themselves are lacking.’

– Umberto Eco

Foreword

Eileen Myles

I’ve been gloriously wandering through Gail Scott’s Heroine for a month. I brought it with me to Norway where I created a temporary reading space in order to make my residency be something social. About twenty of us were seated in the beautiful room silently reading for a few hours. At the mid-point of our activity about one thousand young people began marching right below us framed by a wall of windows that faced the lake in the middle of Bergen. Their cheers distracted us and we happily looked up at one another and then some of us actually got up from our chairs and looked out, standing by the window.

The spirit of that moment (and I knew it then) is the perfect flow through to Gail, whose writing is one you want to tell things to. The only way to read Heroine is to be in it. A few days later I was in London and I made a note to tell Gail (the book) about the people praying in the café this evening.

So what I mainly want to assert is that Heroine is a work of reading then of writing, it is all studio by which I mean it’s something fabulously risky and alive. It’s literature and the possibility of it. Though I might do better stating it in the more eloquent and humble way Gail Scott does:

Refusing to explain how I’m using this place for an experiment of living in the present. Existing on the minimum the better to savour every minute. For the sake of art. Soon I’ll write a novel.

And that is her character speaking, in the book.

Heroine exists between these quick references to the existence of, the anticipation of ‘the novel,’ the utopia of it and its delayal strewn here and there in order to cinch a moment, to punctuate thoughts, or to simply make an exit, scene to scene, and always offering a soft ending to the book which occurs multiple times in a heaven that’s always ‘here.’

Though the actual ending of this book is one of the best I’ve ever read.

The narrator of what Scott calls ‘my most novel-like novel’ is of course the young Gail Scott. She wrote it from 1982 to ’86 so she’s in her thirties. I guess. The Heroine has a playful, thoughtful, self-deprecating and idealistic character and she’s not above making a drug joke:

I have to pull myself together. To get a fix on the heroine of my novel.

The writer had once been a journalist. The writer of Heroine is in between. Between women and men, between activism and lying in her tub.

She’s a perfect … let’s say a Claire Denis character. A woman zigzagging between the affections of women and men – in the time of the novel more affiliated with men but actively engaged in the widest definition, most contemporary version of feminism which of course included sex (with women).

And this is all occurs in two languages, mainly English but enough French that I’m constantly on my phone getting some very awkward translations. I want to jump you. Huh.

I finally emailed Gail Scott to get a handle on the politics and the linguistic world of Heroine and its time and who are you in that I asked.

First she spoke in general terms. Gail Scott reported perhaps about her entire career:

Sometimes I think of all of my work as unbelonging (but not in a faux outsider way; just too many threads to take sides).

Her narrator it struck me would speak with such conviction, being so much more entranced by living.

She explained that she, Gail, is an anglophone writer, a condition determined ultimately by which language you speak at home. But where’s that?

I’m thinking of the novel now because politically she was also living in French, being engaged then as she put it:

with a group that was a faction of the independentist left, in other words not nationalist per se but believing independence from Canada was the best way to have enough control over our affairs to establish a socialist Francophone society.

And in tandem with that having several French speaking and male lovers. Now this was pretty radical to me.

Meaning that rather than encountering an early work by a major female Canadian author from their naughty lesbian phase, instead we are rambling through the more conventional corridors of that same author’s historic normative relations with men. It is not her adulthood, it’s late youth. The described experience is certainly romantic but also in effect constitutes research into the political history of women and men (aka Patriarchy). Delightedly I conclude that our heroine grew up and away from all that.

The Heroine’s relationships with women here are more or less affiliated with feminism, conversations thereof tinged with implied sex always dangling like a paradise or the carrot of the novel, and these relationships are inherently more intense because one was a woman and those relationships had a different capacity to split her open whether they were sexual or not. Women just have a way to look deeply, critique and challenge, hug, massage, conciliate, and shrug. It’s a more complicated machine. Whereas with men the relationships are deeply comfortable in a fleeting, provisional way. Each time it’s a little bit like catching rabbits – opening the cage and holding the creature in your hands, looking into their pink eyes and wondering if I really want this one.

And then you might look out the window (in the novel) at the startling fact of the world:

The tree skeletons have melted into the beautiful night sky.

Or:

…the blackness of the leaves hanging so heavy over the sidewalk that the Hebrew school with the Star of David across the street is obfuscated. Barry’s on the waterbed. His head leans against a crazy piece of plaster-moulded flowers on the wall. (Their all-white, old-fashioned flat is full of crazy details, typical of Montréal houses from the early century.)

Her camera heaves closer and closer into rooms and back out into the street. And even further. Who is the mysterious Black photographer, a tourist, who is sometimes seen shooting the world of Heroine from above, standing seemingly on one of the hills or the hill that Montreal is named for.

Heroine leads me out of itself to think about other books which also managed in their way to deploy the real experience of living in a precise time whether that was their intention or not. I think of Joe LeSueur’s memoir Digressions on Some Poems by Frank O’Hara which was LeSueur’s rejoinder to Brad Gooch’s City Poet which was my generation’s exploration of the O’Hara myth. LeSueur meant to set the record right and what he accomplished Gail does in spades here. She’s obsessed with time, cultural and local. If the 50s was a coterie time and the 60s were immersive and the 70s were a decade setting up networks but still kind of in shock

that the totalizing previous thing (the sixties) had truly passed, what Heroine reveals about the 80s is so much cultural standing in the mirror and wondering if it was real or not, fitfully beginning (just as it was beginning to end) the obsession with decades. Everybody, whether they were engaged in political action in the streets, or in bed, or at dinner with their friends was also standing in the mirror holding one another and trying not to do it wrong whatever the present is. Because that present (and this is the unique almost fibrous knowing Heroine is made of) could see in a very non-techno way its own collective aura fleeing. So Gail’s novel-like thing, this masterfully transitional book, is the quintessential medium to be looking through at that. Which it is.

Act British, she admonishes herself while being watched by her lover and his other lover (a woman) as she steps dripping out of the shower. It was so matter of fact. In this book we know Gail’s ass. Like she knows it.

And the tub is cited in Heroine just as often as the novel. I’ve got to get out of the tub right this minute. Perhaps it’s the novel’s more earthly counterpart. Thank God for the tub.

And for clothes.

Over the faded olive jumpsuit (it’s a bit silly to dress so badly) she puts on the old fur jacket. Then steps out onto the front steps covered with green turf rug and a layer of snow.

She is movement. In cafés and cars with friends and standing out in the street observing the many hookers who also come into the cafes. Hookers are the chorus of this book. There are homeless people too, a single grey woman who returns again and again, but the hookers, all of them, are her other.

The hooker is radical. Her political other. Gail’s collective shadow. Exactly caught in the gate of capitalism, dancing, changing her clothes trying to be invisible, making a deal while being the most visible one of all, and somehow always they not she. Has the non-binary nature of sex work ever been explored. The notebook is here and open.

I

BEGINNING

Sepia

Sir. You can on-ly put ca-na-dien monee in that machine. No sir. No foreign objects nor foreign monee in that macheen. It’s an infraction, you see. The guard’s finger runs tight under the small print. The wooden squirrels in the rafters are si-lent. The Black tourist descends the steps with an astonished stare toward the telescope aimed at the city skyscrapers.

I’m lying with my legs up. Oh, dream only a woman’s mouth could do it as well as you. Your warm faucet’s letting the white froth fall over the small point on the tub floor. Your single eye watches my floating smiling face in its enamel embrace. Outside the shops swing. The wind has turned the trees to yellow teeth. This is the city. Montréal, P.Q. I work here. I’m a c—

That is I worked here ’til one day. I was sitting in that Cracow Café on The Main with its windows and walls sweating grey against the winter. Eating steamies made from real Polish sausage. Suddenly I looked up and there was this funny picture. A cross stuck in a bleeding loaf of bread. You were sitting under it smiling at me through your round glasses. Sort of, with your wonderful mouth, so feminine for a man’s. And your beat-up leather jacket.

Some hookers were standing round drinking hot chocolate. One was so wired up she kept doing a high step still holding her cup. Right leg over left leg. Twice. Left leg over right. There was no point trying to stop her. Somehow you managed to slide out over the torn red plastic seat and sit down beside me. Without anybody seeming to mind. I loved the smell of your cracked leather jacket. From Europe with love.

No, I’m telling stories. Maybe these women were your socialist revolutionary comrades trying to get stopped for soliciting so they could expose the brutality of the city administration. Some of them had middle-class skin.

I mean solidarity. If anyone asks, instinctively I have the answer. Loving women. In my case two. That is, the same set of brown eyes twice. We’re side by side on her bed. Then I’m lying on top of her soft breasts. She pulls up her white nightshirt and pulls down her panties so our genitals will touch. I – I think I rolled off. Yes it was me who stopped. Knowing I’m a failure. No. Never admit. Never admit you’re a failure.

The smell of coffee. Real cappuccino. A few leaves rush by a real prostitute bending her knees ’til her pussy comes forward. Then putting her hand on it. The harsh note is in the next booth saying: ‘She should adopt a more self-critical voice.’ His woman companion nods but her answer’s drowned in the noise. ‘You have a relationship,’ the guy is saying, ‘and you learn something from it. Next time you select better, that’s all.’ He shrugs. We get up to go. I like how your glasses hang on a string. When you’re not wearing them. Later, looking at the photos, I notice we’ve seen it all the same. The pretty prostitute, her jeans just right snugly over the V-shape but not too tight – Um, your hands reassure me. Confidently clicking the camera. Together we’re crossing the bar of light.

Colder times are coming. The Black tourist sees the plain whiten beneath the skyscrapers. The scene shifts to that dome-shaped café full of hippies and women in cloche-shaped hats. The sign says BAUHAUS BRASSERIE. It only fills half the lens. Jane Fonda goes by on a horse spattered with the blood of Vietnam. A gay man is fingering my homemade leather blouse and saying: ‘Sweetheart, you look so much like Barbarella.’ The new man and I get up to go. As we step out into the snow a woman comrade cries: ‘How come you never kiss anyone but her anymore?’ I’m a bit scared. We’re standing in the harbour. The gulls clack in the fog over the old schooner. I can’t hear my breath. Maybe we’re coming in unison. The illusion of perfect fusion. ‘Gail’s friends are my friends,’ you say in a soft voice. I’m so relieved. It’s starting to snow. Of course I didn’t know what you mean when you say that. Until I looked back and saw her head on your shoulder. Across the room at Ingmar’s when the sun shining through the lead glass delineated that dark place under your chin where it felt so safe. I’d been running from chair to chair on those Marienbad squares asking: ‘Have you seen Jon?’ as if I didn’t care. Suddenly she’s standing in front of me saying: ‘Why don’t you just relax?’

She’s right, Sepia. What I learned from her is that the relaxed woman gets the man. That was in the summer of ’76. When the RCMP hinted our group should leave the city if we didn’t want any trouble. The whole Montréal left was on the train. We called it our Olympic Vacation. Going to visit the other so-called Founding Nation. On that trip you’re in the woods for a good two days. Deep in reserve country with the trees leaning recklessly over the horizon. My legs were so anxious I wanted to jump off. Because I couldn’t forget the restaurant scene where someone said at the next table: ‘Elle a perdu; qui perd, gagne.’ I wrote faster. So fast and so small you could hardly see my handwriting. The cop at the counter watched as if I were writing in code. His handcuffs were at his belt. The gulls flew over the glassed-in roof. You used to sit there and think of sound, of the ships battering up and down between the waves. (I loved your mouth; it held me to you when the rest of your body cut like a knife.) You said: ‘I want to be free. No monogamy. It’s not for me.’ I laughed and pulled out my plum lipstick. ‘Tea for two,’ I said. ‘Decadence for me and decadence for you.’ No wonder you looked surprised. It wasn’t the right reaction.

Anyway, we were on the train. When suddenly I was awakened by an angel in a turquoise blazer. She held a CN card in her hand that said: WHILE ON THIS TRAIN YOUR WISH IS MY COMMAND. We watched her disappear in the night. Noting we’d forgotten to say the heat was pouring out from under the seat. Though it was the middle of summer. We never saw her again.

But I couldn’t get back to sleep. I was so worried about not being able to smile when the girl with the green eyes put her hand on your thigh.

A feminist (I kept repeating)

cannot be impaled

by a white prince.

The trip was like a dark tunnel. At the other end there would be light. When I got to Vancouver, I’d see, maybe, how to be free. Janis Joplin came on the radio. Her voice cracked like one of those evergreens trying to grow on

the burnt earth outside Sudbury. She said: There’s no tomorrow, baby (laughing her head off). It’s all the same goddamned day. We learned that coming here on the train.

The Dream Layer

’Tis October. On the radio they’re saying ten years ago this month Québécois terrorists kidnapped the British Trade Commissioner. I was at my kitchen table. Through my window the mellow smell of autumn leaves in the alley. Making me slightly ill due to a temporary pregnancy. A drunk wove along the gravel. I was just wondering how to put it in a novel when the CBC announcer said: ‘We interrupt this program to say the FLQ has kidnapped Britain’s trade representative to Canada.’ I couldn’t help smiling. Even a WASP, if politicized, can recognize a colonizer. Besides, the crisp autumn air always made me restless. Later, my love, we laughed so hard when the tourist agent told the group from Toronto looking for cultural manifestations in Montréal: ‘Eh bien ici les manifestations ont lieu d’habitude au mois d’octobre.’ Winking at us in line behind them (we were going to Morocco). For in French manifestation also means political demonstration. He meant the October Crisis and other assorted autumn riots. People were freer then.

Alors pourquoi Marie a-t-elle dit que je ne serai pas au rendezvous? She meant on the barricades of the national struggle. Her face had this funny look, half guilty, half cruel. (She was still in the revolutionary organization then.) Even hinting that my grandfather might be Métis didn’t convince her. Of course I didn’t tell her and the other comrades the family kept it hidden. Why should I? They must have guessed anyway, because M, one of the leaders, tugged his beard and said: ‘We’re materialists. We believe one is a social product, marked by the conditions he grew up in. You’re English regardless of your blood.’ We were sitting in the revolutionary local. Around the table no one said a word. Even you, my love, I guess you wanted to keep out of it.

Heroine

Heroine