- Home

- Gail Scott

Heroine Page 2

Heroine Read online

Page 2

Marie’s face had that funny look again today when she came to visit. She was wearing an immaculate silk scarf. Over it her nose turned aside as if offended when she saw the state of my little bed-sitter. Granted, it’s kind of tacky. Green patterned linoleum and an old sofa. In the bathroom, black-and-white tiles like they have in the Colonial Steam Baths. Except some are falling off. Trying to make light of it, I said as we stepped into the room: ‘Ha ha, the hard knocks of realism.’ She didn’t laugh. She didn’t even smile ironically. So I decided to hold back. Refusing to explain how I’m using this place for an experiment of living in the present. Existing on the minimum, the better to savour every minute. For the sake of art. Soon I’ll write a novel. But first I have to figure out Janis’s saying There’s no tomorrow, it’s all the same goddamned day. It reminds me of those two guys I once overheard in a bar-salon: ‘Hey,’ said one, except in French. ‘Did you know the mayor’s dead?’ His lip twitched. ‘No kidding,’ said the other. ‘When?’ ‘Tomorrow, I think.’ They both laughed. Sure enough the next day on the radio they said the mayor was at death’s door. Nobody knew why. City Hall was mum. Rumour had it there’d been an assassination attempt by some unnamed assailant. I felt like I’d seen a ghost.

I got that same feeling again later taking a taxi along Esplanade-sur-le-parc. On my knee was the black book. The budding trees were whispering, the birds were singing: a beautiful spring eve. (Like when we first fell in love, my love.) When suddenly on the sidewalk I see a projection of my worst dreams. A real hologram. You and the green-eyed girl. Right away I notice she’s traded in her revolutionary jeans for a long flowing skirt. And her hair is streaked. Very feminine. As for you, you’re walking sideways, the better to drink her in. With your eyes. Oh God, obviously you can’t get enough. The taxi dropped me at the bar with the little cupid holding grapes in front of the mirror where I was going to meet some gay writers. One of them said: ‘Chérie, you look terrible.’ I was speechless. All I could think was what a coincidence. Because at the moment I saw you, my love, I’d been writing in the black book (not believing yet that our reconciliation was really finished): He’s Mr. Sweet these days. I’m the one who’s fucking up, making scenes. Oh well, tomorrow’s another day.

‘Qu’as-tu?’ asked Alain. He has green eyes like my father, but he wears jewellery.

I said: ‘I think I’ve seen a ghost. Real-life from a nightmare I once had. Everything back exactly as it was.’

‘Trésor,’ dit-il, ‘la science dit que la répétition n’existe pas. Les choses changent imperceptiblement de fois en fois. Maintenant tu vas prendre un bon verre.’ I didn’t reply, concentrating as I was on how to be a modern woman living in the present while at the same time finding out who lied, my love, me or you?

A delicious warm sweat is forming on the bathroom tiles. Through the open door I see the dented sofa where Marie sat this afternoon. Determined as ever with her flat stomach and her straight back. In that immaculate white silk. Suddenly she put her hand over her mouth, as titillated as a little girl who’s caught a glimpse of something unspeakable. I knew it was that place above the stove where the dirt adheres to the grease, working the paint loose until it starts to peel off. And she was about to criticize my housecleaning. To ward it off I focused on how growing up over that dépanneur in St-Henri probably made her fussy. Every Monday and Thursday after school she had to take off her blue tunic and scrub and scrub the slanting floor under the domed roof. What got her was the darkness of the courtyard. You could feel it from the kitchen window. One day, walking in there she found a big rat lounging on the table. Slowly unwinding his virile tail, he looked at the little girl with his small eyes and said: ‘Mademoiselle, voulez-vous me ficher la paix?’ In International French. She couldn’t think of a thing to say. None of the neighbours spoke like that. Later, she thought it was a dream.

Glancing only slightly in my direction, she blurted it out in spite of herself: ‘Tu pourrais faire un peu de ménage. On dirait que tu n’as plus d’amour-propre.’

I kept silent. It’s better than saying: ‘What about you? You’re too obsessed with how things look.’ Besides, as I’d decided to take a bath, I was busy with my ablutions.

I guess I lost track of time. Because I didn’t see her get up and say goodbye. I realized she hadn’t said anything about coming back.

Colder times are coming. In the telescope the plain whitens. The tourist sees a field of car wrecks below the skyscrapers. A woman is walking toward a park bench. Suddenly she sits, pulling her coat down in the front and up in the back in a single gesture so you can hardly tell she’s taking a pee.

Oh, faucet, your warm stream is linked to my smiling face. Outside the shops swing: peanuts, blintzes, Persian rugs. Marie m’a dit: ‘Tu as payé avec ton corps.’ Shhh. Reminiscences are dangerous. Who said that? Never mind. When I get out of here I’m going to throw out those old pictures on the stool by the tub. That one half-hidden in the folds of the second-hand lime-green satin nightgown must have been taken in Ingmar’s courtyard. Black and white with a silvery grey light shining on the shoulders of our dark leather jackets. We were the perfect revolutionary couple, tough yet happy. Leaning together after a walk in the Baltic fog, eating almond-cream buns. Except at Ingmar’s somebody almost stole the silver plate from me.

What went wrong wasn’t obvious. Earlier, travelling in Morocco, everything seemed perfect. The magic was in slipping out of time. No landlords, no waiting for you to phone, my love. The air was filled with spice, roast lamb, mysterious music, the delicate odour of pigeon pie. From our hotel room we heard an Arab kid with a knife offer to make a rich woman tourist high for a price. We laughed as his voice mocked her under the arch of the starry sky (’twas in life before feminism). I loved our mornings. Honey and the smell of Turkish coffee in the huge café at Poco Socco. With the passing donkeys and men in felt hats and beautiful djellabas obscuring our view of the rich American junkies on the other side, I wrote a poem:

the music of your tongue

slides between my lips

the tongue of your sandal

between my toes

glides through the grass in the orange grove

there has been a communist purge

a dead scorpion lies upturned

on the road to the fortress

Then we were heading northeast across the desert. After a day and a half, the train rolled into flowered vineyards, then the city of Algiers. In a lighted square, a white-clothed man with a thin dog leaned back, playing his flute to lions of stone. Stepping off the train, a plainclothes cop arrested us. It was midnight. He led us out under the Arabian arches of the station. Saying it was for our own protection. Because the streets at night are dangerous. ‘God,’ I thought, ‘somehow they’re on to the fact we’re into heavy politics back in Montréal. What if they find the poem with the word ‘communist’ in my purse? Now I’ve really blown it.’

The police station was plastered with pictures of missing children. Beautiful girls and boys of all ages. Probably sold to prostitution. That’s racist. They let us spread our sleeping bags in the same cell. When in the morning they said: ‘You can go now,’ my love, I was so relieved it seemed that anything was possible. So at a fish supper in a fort restaurant on the middle corniche where Algerian freedom fighters had daringly resisted the French, I said: ‘You’re right to be against monogamy. As long as we trust each other anything’s okay.’ Through the open window I saw a beautiful brown man, naked from the chest up. He was looking in, holding a fish net. As if he’d emerged from the sea. ‘Anyway,’ I added, ‘the couple is death for women.’ You smiled with your wonderful soft lips. We headed north. In the mirror of a hotel room in Hamburg, you took a self-portrait.

Everything was perfect.

Except, at Ingmar’s, your mother’s boyfriend’s winter house on the Baltic, something started going wrong. That particular morning, I must have been dreaming. Because lying back I saw a face looking through a window, smiling. Vi

nes around its neck. Glistening as though it had risen from the sea. Only, outside a slow brown river ran. It was the city. Pink lights on tall white buildings. Red and yellow streets. I woke up to a winter morning. Shadows of noir et blanc. Smell of coffee in a china cup. Bluish tile cooker reaching to the ceiling, Northern European style. Yes, everything was perfect. So why at that precise moment did I get up, open the cooker’s little brass door, and throw the photos of your former lovers in the fire? Just as you came in.

Your silence left me confused. All that European retinue across the winter room. Then the Modigliani print on the wall behind the golden strands of your hair reminded me I needed a man like you to learn of politics and culture. I’d have to try harder. Thank God, despite my error, our days continued to be wonderful. Walking white streets eating almond-cream buns. The falling snow giving an air of harmony. Yet under that blanket of perfection (we were a beautiful couple, everybody said so) the warmth seemed threatened. As if I couldn’t handle the happiness. Secretly the darkness of the closet beckoned. I wanted to sink down among the silence of your coats. (Good wool lasts forever.) Your mother, turning her head from a conversation with her son, said to me: ‘À quoi ressemble ta famille?’ I saw the smokestacks of Sudbury. And her emaciated face sitting on the veranda. ‘Fine,’ I answered, smiling broadly as if I didn’t understand the question.

The feminist nemesis was that the more I felt your love the harder it was to breathe. In Hamburg, when the subway stopped between two stations and the lights went out, I began to sweat. Pins and needles pricked my chest so much I wanted to grab your sleeve and say: ‘Help, please.’ But hysteria is not suitable in a revolutionary woman. Thank God a winter-shocked unemployed Syrian immigrant started to bark. His family gathered round him laughing nervously. Eyeing back the fishy stares of other passengers as if it were a joke. As if it were a joke. My fear of crowds at demonstrations was harder to conceal. Although you’d have been initially forgiving. Because paranoia in new politicos is normal. Given how scary it is to become conscious of the way the system really works. Anyway, following that little blow-up at Gdansk, when we went to a local march in solidarity, I heard the press of soldiers’ feet behind us. Someone yelled: ‘To the church, to the church!’ My love, the crowd was barreling down so heavily that when they closed the huge oak door I was out and you were in. How could you have let it happen? How?

It wasn’t the right question.

The peace in a foreign place was visiting your grandmother. Behind the winter-spring light she stood in her embroidered apron. I said: ‘Hers is the last generation before occidental cultural homogenization, dominated by America.’ You looked up, interested. Just then your cousin came into the room. Behind her glasses I detected an infinite sadness. ‘Gertrude’s dead,’ she said. ‘We think she killed herself because of Lenz. He was having an affair.’

I quickly checked the woman in the mirror over the mantel. She had straight bangs and a well-cut raincoat. It couldn’t happen to her. Although I’d have to play it careful now, given how weird I felt. The trick was to sit straight in my chair (like a European woman), carefully modulating my voice when we disagreed so as not to sound aggressive. You hated a lack of harmony. Unfortunately, my old self-conscious laugh came creeping back. Especially after your high-school girlfriend came for a visit. Watching the two of you dance over the Marienbad squares, with her head in that safe place under your chin, I felt like screaming.

Suddenly you grew cooler. Wound up as I was, I didn’t see at once that I was spoiling things by trying too hard. Not until I read about the German guy they wrote of in the paper. He wanted a driver’s licence more than anything in the world. Due to the fact he’d stayed home on the farm to take care of the folks and needed a way out. Just to make sure he wouldn’t fail, he practised in the backfield for several years. Then he passed the test without a hitch. The tragedy was that driving home down a country road he hit a girl. In the dark and pouring rain she seemed dead, so he buried her in the streambed. Incriminating evidence must stay below the surface. After that he tried harder when he hit another, backing up and having several other goes, before sending her, also, to her final repose in the sand under the little river.

I’ve got to get control. Lying with my legs up I see the whole picture in my head. As infinite as unsullied snow. Then a man walks over it dragging an iron-runnered sled. The hard knocks of realism. The dark arpeggios on the radio blend with the sirens outside. Janis is singing that if you love someone so precious their beauty cannot be had completely. If someone comes I’ll turn it off. So no one can say: ‘You’re stuck in the past. In his photos of Morocco; in his images of love.’

That’s what Marie said once. Her exact words were: ‘Il faut choisir. Car une obsession, c’est l’hésitation au point d’une bifurcation.’ We were sitting in Figaro’s Café, circa 1977, looking at a picture of your other woman. My alabaster cheek against her olive one.

The unfortunate thing is, Janis just happened to come on the air this afternoon when Marie was here. Singing ‘Piece of My Heart’ (Take it! Take it!) Reinforcing the impression I was still living in my own soap opera. With an irritated rattle of her silver Cartier bracelets, Marie reached over and turned it down. Through the partly open bathroom door, I watched to make sure her Grecian profile didn’t look toward me and say: ‘Pour moi ta vie prend les airs d’une tragédie.’

She already said that once. A beautiful summer evening, and I’d just come up the sidewalk in my red flowered skirt. Holding out some sparkling cider and a rose for her. She, standing in the doorway, said, smiling: ‘Tu as les petits yeux pétillants, pétillants, pétillants.’ Then her face darkened and she showed me a scientific astrological analysis of how women with my birth date often end badly. The example was Janis, born on the same day. Dead of an overdose. I said: ‘Yeah, but she died famous.’ Sepia, what scared me was the look in Marie’s eyes. As if she knew something terrible would happen. I could only think, my love, that it was in regards to you. So I added nonchalantly: ‘Anyway, to the victor belongs the spoiler.’

I’m sorry, my love. You were a new man who tried. I just wish you hadn’t always spread yourself so thin. At the time it was hard to argue. For when I said: ‘Charity begins at home,’ you said: ‘That isn’t communist. What interests us is collective life.’ And I could hardly deny the veracity of your statement. The only solution was to find another way to pose the question. Marie said: ‘Nous sommes des femmes de transition. En amour, il nous faut éviter la fusion. Évidemment, this leaves a woman pretty empty. I see no other thing to do but write.’ I knew what she meant. Putting one word ahead of another on the page gives a feeling of moving forward. I started thinking of the novel I would do.

To get in the mood, when I get out of this tub I think I’ll go to that artists’ café. The young men sit there every day in black leather jackets and headbands, watching the leaves blow across the street. The bubbles coming from the coffee machine warm the cockles of a single woman. Have to be careful what to wear. In case I meet you and the green-eyed girl. No. The trick is not to be defeatist. Inside the café the smell of coffee is encouraging. A lesbian sings of love in a telephone booth. Her voice rings above the clatter of dishes. This morning an artist was screaming: ‘Those fuckers didn’t give me a grant.’ He meant the government. He was pounding the table with his left hand. Before smiling to himself and drawing circles on his movie program. Outside, an old woman was rubbing her stomach as if hungry. He flicked his cigarette at her. It stuck on the orange neon sculpture advertising the work of another painter. She threw back her toothless head and laughed.

My little room is so quiet now. You can almost hear the snow falling on the sidewalk. I’ll just turn on the radio. Tonight they’re doing that retrospective of women singers, maybe Bessie, Edith, Janis. All their biographies end badly. That won’t happen to the heroine of my novel. She was pretty sure of that when (at twenty-five) she climbed off the bus from Sudbury. The smoke hung stiff in the cold sky. At

Place Ville Marie she found the French women so beautiful with their fur coats and fur hats under which peep their powdered noses. If anybody asked, she’d say she wanted a job, love, money. The necessary accoutrements to be an artist. She immediately rented a bed-sitter. Stepping off the Métro that night and turning a corner, she saw the letters FLQ screaming on an old stone wall. Dripping in fresh white paint. Climbing the stairs to her room she knew she’d come to the right place. She just needed some friends. She started looking in the downtown bars, working east to St-Denis. Then up The Main. It took a couple of years.

My love, those pictures you took of us on the Lower Main marked the start of my new era. In them I look so happy, so free. Even the dilapidated bars in the background have this silver glow. We’re walking from the Lower Main north, your camera clicking all the way. You take one of a guy at the corner of Ste-Catherine pissing in the wind. I remember wondering if it felt good. In front of the Lodeo some Anglo junkies I’d seen hanging around the art galleries wait for a fix. The next shot shows me explaining how artists from rich minorities like les Anglais du Québec need marginal lives in order to feel relevant. My black-gloved hand gesturing in the air. You nod, interested, backing up the street, your eye trained on me through the lens. We enter the Cracow Café. The women have pale faces and dark coats over their shoulders.

I could start the novel here. At the Cracow Café, but a little earlier. Just before we met. I felt something stir in me as soon as I walked in. You were sitting under a Polish poster drinking coffee from a thick cup. Lennon glasses on your pretty nose. From the end of every booth a wooden hand beckoned clients to hang up their coats. You had the sweetest smile I’d ever seen on a man. My first thought was this was exactly what I wanted. You and the others sitting there in wire glasses and smoking hand-rolled cigarettes. Obviously involved in some heavy intellectual discussion. Then the usual moment of doubt when a person naturally draws up a litany of why she’ll never rate. No class. Because in Lively, near Sudbury, a retired mining foreman is something but with an intellectual like you it would be less than nothing. At the time I wasn’t political enough to know of your attraction to the working class.

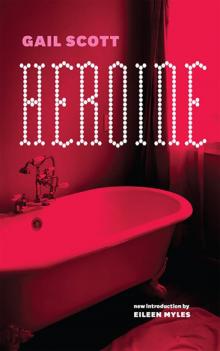

Heroine

Heroine